Giganotosaurus: Cretaceous Terror Of Argentina

Giganotosaurus carolinii (commonly misspelled as “Gigantosaurus”) was a giant theropod dinosaur from the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 100-97 million years ago. Located in what is today South America, specifically Patagonia in Argentina, which has been the site of many large dinosaur discoveries in the past 30 years or so. Although fragmentary, the image created from the fossil remains reveals a powerful, streamlined predator with knife-like teeth, a body built for speed, and a size worthy of a name meaning “Giant Southern Lizard”.

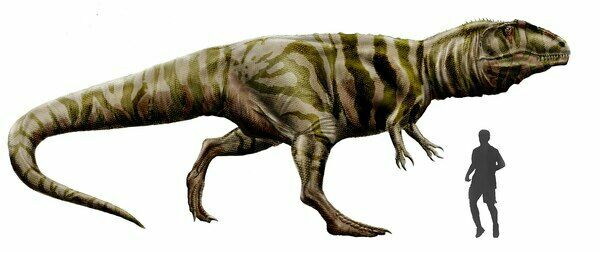

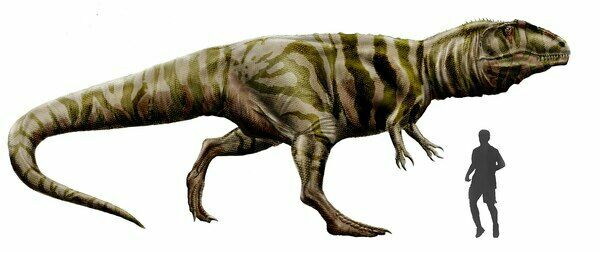

Rendering of Giganotosaurus carolinii with human for scale. Image Credit: Durbed (Creative Commons License)

Giganotosaurus was one of the first known theropods in the group that would later be named the Carcharodontosaurs. It was the largest member of this group.

At an estimated 40-43 feet (12-13m) in length, Giganotosaurus made waves upon its discovery as one of the first carnivorous dinosaurs known that could have matched or even exceeded the size of Tyrannosaurus rex.

“Giganotosaurus carolinii” means “Carolini’s Giant Southern Lizard”, in reference to its large size and its discoverer, Rubén D. Carolini, an amateur fossil collector.

After its discovery, many more complete Carcharodontosaurids were discovered, all of which reach similar large sizes like Giganotosaurus.

Giganotosaurus itself is known only from the remains of two individuals, a fragmentary skeleton representing one, and a lone dentary bone from the lower jaw representing the other. Much of what we know about Giganotosaurus is inferred from related species like Mapusaurus.

Giganotosaurus is only known from the Candeleros formation of Argentina in South America.

Going by its jaws, Giganotosaurus likely had a weaker bite than a Tyrannosaur, but its teeth were flatter and more built for cutting. This, coupled with its reinforced chin, suggest an active predator that carved huge chunks of soft tissue from its prey.

Based on the related Mapusaurus, it is entirely possible that Giganotosaurus may have worked with other members of its species to take down larger prey animals, like the titanosaurs it lived alongside.

Until the discovery of more complete Spinosaurus remains in the early 2000’s, Giganotosaurus was considered the largest theropod dinosaur in the southern hemisphere, and possibly the world.

Giganotosaurus was initially spotted in 1993 by amateur fossil collector Rubén D. Carolini from a tibia jutting out of the stone in the Neuquén province of Patagonia in Argentina. From this discovery, researchers from the National University of Comahue were notified, and with the funding of science writer Dom Lessem, the full fossil was able to be unearthed.

This original specimen comprised 70% of the skeleton, although the fossil itself was disarticulated and scattered over a wide area. The skull alone was very fragmented and spread over an area of about 110 square feet. Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado, the lead paleontologists who uncovered the remains, dubbed the specimen “Giganotosaurus carolinii”, meaning “Carolini’s Giant Southern Lizard”, honoring Carolini as the discoverer and the genus name denoting the massive size of the animal. At the time of its discovery, Giganotosaurus was the largest known theropod from the southern hemisphere, and possibly in the world.

In 1995, the discovery of the related dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus in north Africa revealed a similar body size, and further studies of the family “Carcharodontosauridae” revealed a derived family of 11-13 meter (35-43 foot) monster theropods, most rivaling (or in Giganotosaurus’s case, possibly exceeding) Tyrannosaurus rex in size.

Giganotosaurus made waves after its unveiling to the public, with the original holotype specimen on display in the Ernesto Bachmann Paleontological Museum in Villa El Chocón, Argentina, alongside a replica mount of the restored specimen. The discovery of Giganotosaurus and its relatives helped paleontologists broaden their understanding of Cretaceous large theropod evolution. Prior to that point, there were no T.rex-sized theropods known from the southern hemisphere, and the northern hemisphere at the time would have been contested between earlier, smaller tyrannosaurs and larger theropods, like the neovenatorids.

Giganotosaurus was, at the time of its discovery, the largest known theropod from the southern hemisphere, and some estimates placed it as the largest theropod on Earth. Current size estimates based on the measurements of the restored material place it at roughly 12-13m (40-43 ft) and about 7-8 tons. For comparison, Tyrannosaurus rex was also about 12-13m (39-42 ft) and on average about 8 tons, but larger specimens have been found that exceed 9 tons.

In the present, we now know that Spinosaurus is longer than both Giganotosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, but Giganotosaurus’ true size is still a matter of question. It is no doubt an enormous theropod, and length estimates are consistently in the 12-13m (40-43 ft) range, however the fragmentary nature of the remains and in particular the skull make more accurate measurements difficult. For example, the generally accepted weight for the known adult specimen of Giganotosaurus is about 7.5 tons, with a slightly larger individual known only from a dentary estimated at about 8 tons. However, historically, weight estimates for Giganotosaurus using different methods have varied between 5 and 15 tons, possibly far exceeding T.rex if the larger estimates are taken into account. However, these larger estimates are typically considered exaggerated.

It may have developed such a large size as an adaptation for hunting the enormous titanosaurid sauropods that it lived alongside. Currently, only 2 individual specimens are known of Giganotosaurus, and one of them is only known from a large portion of a single dentary bone. This makes averaging impossible, and is a poor sample size for making any generalized statements about the species. Until more Giganotosaurus remains are found, much about their growth and maximum size will remain a mystery

As a large theropod, Giganotosaurus was the apex predator of its domain, hunting and eating any other animals it could catch. Its large head, which was possibly longer than T.rex’s, was filled with sharp teeth with fine serrations on both edges, and had a robust chin, possibly an adaptation for withstanding strong impacts.

It had a bite weaker than a similarly sized tyrannosaur, however its teeth were more functional for slicing, and it had a much wider range of sideways motion in its jaws, which may have aided it in cutting deep wounds into its prey. Its bite was strongest at the front of the mouth, which would have aided in tearing. Its legs were longer, and more adapted for running than an adult tyrannosaur’s, suggesting that Giganotosaurus was more adapted to a pursuit style of predation. These adaptations in conjunction paint a picture of an apex carnivore that would have fed on anything of sufficient size to sate its hunger. Some have suggested that Giganotosaurus would have regularly hunted and eaten juvenile or even adult titanosaurs.

No juvenile or subadult specimens are known from Giganotosaurus, so its growth rates are not known. If we assume that Giganotosaurus had a similar lifespan to Tyrannosaurus, about 20-30 years at most, then we can likely assume that it had a period of rapid growth at the juvenile stage of its life into adulthood. This is, however, only an inference based on a theropod that is only distantly related to Giganotosaurus.

Interestingly for a large theropod, Giganotosaurus’ eyes were positioned more laterally on the skull than other large theropods, which would have reduced its binocular vision compared to them, though not eliminating it entirely. The enhanced peripheral vision would have given it a wide area of vision, but less focus on depth, which was possibly an adaptation for the flat and wide geography of Cretaceous patagonia.

As stated previously, Giganotosaurus was the apex predator of its environment. It had doubly-serrated teeth with jaws that were stronger towards the front than the back of the mouth, and a streamlined build with long legs built for speed. The related dinosaur, Mapusaurus, which lived just after Giganotosaurus and was roughly the same size, has been found in a large bonebed composed of multiple individuals of varying life stages. It has been put forth that this deposition of remains is evidence of grouping behavior in Mapusaurus, which may extend to Giganotosaurus.

Carcharodontosaurs are often found alongside sauropods, such as Limaysaurus in South America and Paralititan in North Africa. The group of seven Mapusaurus found in the same region as Giganotosaurus suggest that the animal may have grouped together to take down juvenile sauropods, which would have been formidable prey items not easily subdued by a single predator. It is unknown whether this was true pack hunting, in which animals live together in a semi-organized group, or whether this was mobbing, like modern komodo dragons sometimes engage in, where animals will group together for a hunt, feed on the prey together, then separate again.

Regardless of their sauropod-slaying capabilities, Giganotosaurus and its relatives would still have been perilous predators regardless. They could have, and likely would have hunted any animals they could have captured in their jaws. Studies on the related dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus show that the neck and jaws of that dinosaur could have lifted just under 1000 pounds. Giganotosaurus, being slightly larger and more robust, may have been able to lift even more.

Giganotosaurus was unique at the time of its discovery, and initially thought to be a large but primitive theropod. Now, it is thought that the large Carcharodontosaurs like Giganotosaurus were derived from the earlier allosauroids, due to similarities in the general build and skull. Within Carcharodontosauridae, the smaller tribe Giganotosaurini was created to house Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Tyrannotitan as being the most phylogenetically similar to one another.

Large sizes were a fairly common trait in theropod family trees in the Cretaceous period, but until the discovery of Giganotosaurus, it was only Tyrannosaurus that was known to exceed the 40 foot mark. Since then, our knowledge has been greatly expanded by the huge variety of late cretaceous theropods, mostly Carcharodontosaurids. Many Carcharodontosaurs, like Giganotosaurus and its relatives, Carcharodontosaurus and Mapusaurus, reached T.rex sizes, at least in terms of length. Large size was likely an adaptation to the increase in size of prey animals like juvenile titanosaurs. Their jaws being more adapted towards shearing and bleeding would also have helped this, as sauropod bones would have been too large for a bone-crushing bite like a tyrannosaur’s to be effective.

The skull of Giganotosaurus was larger than that of Tyrannosaurus, at 1.6m (5.2 feet) compared to T.rex’s 1.53m (5 ft). In spite of this, it had numerous openings for pneumatic foramen, or air sacs, which would have reduced the weight of the head overall when the animal was alive.

The bite of Giganotosaurus was weaker than Tyrannosaurus’, but would have been perfectly capable of slicing into soft tissue. It was weakest at the back of its jaw, and its reinforced “chin” would have aided in resisting impact force towards the front, suggesting that the Giganotosaurus was no stranger to forward assaults. The teeth of Giganotosaurus were like other Carcharodontosaurs, flat and strongly serrated on both edges. The nature of their teeth is where Carcharodontosaurus and the Carcharodontosaur family got its name, meaning “Shark-toothed reptiles”. These flat, cutting teeth coupled with the triangular shape of Giganotosaurus’ bite would have made its jaws work like an efficient pair of scissors, shearing through soft tissue right into important blood vessels and tendons.

Giganotosaurus was a powerful apex predator, but because of the nature of its remains, little is known about the animal that can be stated generally. Much of what we do know is based on related genera, such as Mapusaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. Until such time as more Giganotosaurus specimens can be recovered, many questions surrounding this dinosaur’s life and behavior will remain unanswered.

Coria, R. A.; Salgado, L. (1995). "A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia". Nature. 377 (6546): 224–226.

Bankrolling A Dinosaur Dig And Unearthing A Giant: The Giganotosaurus : NPR

Sereno, P. C.; Dutheil, D. B.; Iarochene, M.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Lyon, G. H.; Magwene, P. M.; Sidor, C. A.; Varricchio, D. J.; Wilson, J. A. (1996). "Predatory Dinosaurs from the Sahara and Late Cretaceous Faunal Differentiation". Science. 272 (5264): 986–991.

Coria, R.A.; Currie, P.J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118.

Blanco, R. Ernesto; Mazzetta, Gerardo V. (2001). "A new approach to evaluate the cursorial ability of the giant theropod Giganotosaurus carolinii". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46 (2): 193–202.

Canale, Juan Ignacio; Novas, Fernando Emilio; Salgado, Leonardo; Coria, Rodolfo Aníbal (December 1, 2015). "Cranial ontogenetic variation in Mapusaurus roseae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the probable role of heterochrony in carcharodontosaurid evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 89 (4): 983–993.

Currie, P. J. (1996). "Out of Africa: Meat-Eating Dinosaurs that Challenge Tyrannosaurus rex". Science. 272 (5264): 971–972.

Calvo, J. O.; Coria, R. A. (1998). "New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the largest theropod ever found". Gaia. 15: 117–122.

Novas, Fernando E. (2013). "Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 45: 174–215.

Rendering of Giganotosaurus carolinii with human for scale. Image Credit: Durbed (Creative Commons License)

Quick Facts

Discovery

Giganotosaurus was initially spotted in 1993 by amateur fossil collector Rubén D. Carolini from a tibia jutting out of the stone in the Neuquén province of Patagonia in Argentina. From this discovery, researchers from the National University of Comahue were notified, and with the funding of science writer Dom Lessem, the full fossil was able to be unearthed.

This original specimen comprised 70% of the skeleton, although the fossil itself was disarticulated and scattered over a wide area. The skull alone was very fragmented and spread over an area of about 110 square feet. Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado, the lead paleontologists who uncovered the remains, dubbed the specimen “Giganotosaurus carolinii”, meaning “Carolini’s Giant Southern Lizard”, honoring Carolini as the discoverer and the genus name denoting the massive size of the animal. At the time of its discovery, Giganotosaurus was the largest known theropod from the southern hemisphere, and possibly in the world.

In 1995, the discovery of the related dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus in north Africa revealed a similar body size, and further studies of the family “Carcharodontosauridae” revealed a derived family of 11-13 meter (35-43 foot) monster theropods, most rivaling (or in Giganotosaurus’s case, possibly exceeding) Tyrannosaurus rex in size.

Giganotosaurus made waves after its unveiling to the public, with the original holotype specimen on display in the Ernesto Bachmann Paleontological Museum in Villa El Chocón, Argentina, alongside a replica mount of the restored specimen. The discovery of Giganotosaurus and its relatives helped paleontologists broaden their understanding of Cretaceous large theropod evolution. Prior to that point, there were no T.rex-sized theropods known from the southern hemisphere, and the northern hemisphere at the time would have been contested between earlier, smaller tyrannosaurs and larger theropods, like the neovenatorids.

Size

Giganotosaurus was, at the time of its discovery, the largest known theropod from the southern hemisphere, and some estimates placed it as the largest theropod on Earth. Current size estimates based on the measurements of the restored material place it at roughly 12-13m (40-43 ft) and about 7-8 tons. For comparison, Tyrannosaurus rex was also about 12-13m (39-42 ft) and on average about 8 tons, but larger specimens have been found that exceed 9 tons.

In the present, we now know that Spinosaurus is longer than both Giganotosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, but Giganotosaurus’ true size is still a matter of question. It is no doubt an enormous theropod, and length estimates are consistently in the 12-13m (40-43 ft) range, however the fragmentary nature of the remains and in particular the skull make more accurate measurements difficult. For example, the generally accepted weight for the known adult specimen of Giganotosaurus is about 7.5 tons, with a slightly larger individual known only from a dentary estimated at about 8 tons. However, historically, weight estimates for Giganotosaurus using different methods have varied between 5 and 15 tons, possibly far exceeding T.rex if the larger estimates are taken into account. However, these larger estimates are typically considered exaggerated.

It may have developed such a large size as an adaptation for hunting the enormous titanosaurid sauropods that it lived alongside. Currently, only 2 individual specimens are known of Giganotosaurus, and one of them is only known from a large portion of a single dentary bone. This makes averaging impossible, and is a poor sample size for making any generalized statements about the species. Until more Giganotosaurus remains are found, much about their growth and maximum size will remain a mystery

Paleobiology

As a large theropod, Giganotosaurus was the apex predator of its domain, hunting and eating any other animals it could catch. Its large head, which was possibly longer than T.rex’s, was filled with sharp teeth with fine serrations on both edges, and had a robust chin, possibly an adaptation for withstanding strong impacts.

It had a bite weaker than a similarly sized tyrannosaur, however its teeth were more functional for slicing, and it had a much wider range of sideways motion in its jaws, which may have aided it in cutting deep wounds into its prey. Its bite was strongest at the front of the mouth, which would have aided in tearing. Its legs were longer, and more adapted for running than an adult tyrannosaur’s, suggesting that Giganotosaurus was more adapted to a pursuit style of predation. These adaptations in conjunction paint a picture of an apex carnivore that would have fed on anything of sufficient size to sate its hunger. Some have suggested that Giganotosaurus would have regularly hunted and eaten juvenile or even adult titanosaurs.

No juvenile or subadult specimens are known from Giganotosaurus, so its growth rates are not known. If we assume that Giganotosaurus had a similar lifespan to Tyrannosaurus, about 20-30 years at most, then we can likely assume that it had a period of rapid growth at the juvenile stage of its life into adulthood. This is, however, only an inference based on a theropod that is only distantly related to Giganotosaurus.

Interestingly for a large theropod, Giganotosaurus’ eyes were positioned more laterally on the skull than other large theropods, which would have reduced its binocular vision compared to them, though not eliminating it entirely. The enhanced peripheral vision would have given it a wide area of vision, but less focus on depth, which was possibly an adaptation for the flat and wide geography of Cretaceous patagonia.

Hunting and Behavior

As stated previously, Giganotosaurus was the apex predator of its environment. It had doubly-serrated teeth with jaws that were stronger towards the front than the back of the mouth, and a streamlined build with long legs built for speed. The related dinosaur, Mapusaurus, which lived just after Giganotosaurus and was roughly the same size, has been found in a large bonebed composed of multiple individuals of varying life stages. It has been put forth that this deposition of remains is evidence of grouping behavior in Mapusaurus, which may extend to Giganotosaurus.

Carcharodontosaurs are often found alongside sauropods, such as Limaysaurus in South America and Paralititan in North Africa. The group of seven Mapusaurus found in the same region as Giganotosaurus suggest that the animal may have grouped together to take down juvenile sauropods, which would have been formidable prey items not easily subdued by a single predator. It is unknown whether this was true pack hunting, in which animals live together in a semi-organized group, or whether this was mobbing, like modern komodo dragons sometimes engage in, where animals will group together for a hunt, feed on the prey together, then separate again.

Regardless of their sauropod-slaying capabilities, Giganotosaurus and its relatives would still have been perilous predators regardless. They could have, and likely would have hunted any animals they could have captured in their jaws. Studies on the related dinosaur Carcharodontosaurus show that the neck and jaws of that dinosaur could have lifted just under 1000 pounds. Giganotosaurus, being slightly larger and more robust, may have been able to lift even more.

Evolution and Taxonomy

Giganotosaurus was unique at the time of its discovery, and initially thought to be a large but primitive theropod. Now, it is thought that the large Carcharodontosaurs like Giganotosaurus were derived from the earlier allosauroids, due to similarities in the general build and skull. Within Carcharodontosauridae, the smaller tribe Giganotosaurini was created to house Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and Tyrannotitan as being the most phylogenetically similar to one another.

Large sizes were a fairly common trait in theropod family trees in the Cretaceous period, but until the discovery of Giganotosaurus, it was only Tyrannosaurus that was known to exceed the 40 foot mark. Since then, our knowledge has been greatly expanded by the huge variety of late cretaceous theropods, mostly Carcharodontosaurids. Many Carcharodontosaurs, like Giganotosaurus and its relatives, Carcharodontosaurus and Mapusaurus, reached T.rex sizes, at least in terms of length. Large size was likely an adaptation to the increase in size of prey animals like juvenile titanosaurs. Their jaws being more adapted towards shearing and bleeding would also have helped this, as sauropod bones would have been too large for a bone-crushing bite like a tyrannosaur’s to be effective.

Giganotosaurus Skull and Teeth

The skull of Giganotosaurus was larger than that of Tyrannosaurus, at 1.6m (5.2 feet) compared to T.rex’s 1.53m (5 ft). In spite of this, it had numerous openings for pneumatic foramen, or air sacs, which would have reduced the weight of the head overall when the animal was alive.

The bite of Giganotosaurus was weaker than Tyrannosaurus’, but would have been perfectly capable of slicing into soft tissue. It was weakest at the back of its jaw, and its reinforced “chin” would have aided in resisting impact force towards the front, suggesting that the Giganotosaurus was no stranger to forward assaults. The teeth of Giganotosaurus were like other Carcharodontosaurs, flat and strongly serrated on both edges. The nature of their teeth is where Carcharodontosaurus and the Carcharodontosaur family got its name, meaning “Shark-toothed reptiles”. These flat, cutting teeth coupled with the triangular shape of Giganotosaurus’ bite would have made its jaws work like an efficient pair of scissors, shearing through soft tissue right into important blood vessels and tendons.

Giganotosaurus: As Enigmatic As It Is Impressive

Giganotosaurus was a powerful apex predator, but because of the nature of its remains, little is known about the animal that can be stated generally. Much of what we do know is based on related genera, such as Mapusaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. Until such time as more Giganotosaurus specimens can be recovered, many questions surrounding this dinosaur’s life and behavior will remain unanswered.

Reviews

Reviews